In November I attended a Technology Quality Management Roundtable in Auckland co-hosted by the IAASB and XRB. In this article I cover some of the key points relevant to our users, who work mainly in the charities and SME end of the market. I summarise what was discussed that seems relevant to our users, then add my comments.

The split between the big firm approach and the rest of us

There were some concerns expressed that the large, highly resourced mega-firms would perhaps become more dominant because their resources available for AI development far outstrip the resources of smaller players. It seems that the big international firms are scrambling against each other to not be left behind.

From my perspective these firms are caught in a very expensive arms-race, reflecting the winner-takes-all actual AI arms-race. However, because of the security and other risks of AI, such as putting too much reliance on its judgement, and failing to check questionable-at-best output, (such as in the recent embarrassing Deloitte report in Australia), just adding AI tools that are designed, tested, and used safely presents a tremendous challenge. And there may be no real answer to AI hallucinations, apart from there being a “human in the loop” a phrase that came up repeatedly. Perhaps these large firms, auditing very large and complex entities, must use AI to audit AI, but I can hardly see small firms getting left behind by taking more of a wait-and-see approach.

At present AI infrastructure – data centres mainly– are being churned out at an alarming rate, chewing through vast amounts of resources, such as energy and groundwater for cooling, used mostly for tasks that according to one article is like using a “nuclear-powered digital calculator.” This is not paid for by profits as yet but from huge speculative investment. At some point these companies will be expected to turn a profit, and what is now a relatively cheap resource could get expensive and scarce as it begins to reflect its true costs – no longer externalised to low-cost economies and environmental degradation. This could turn around and bite those who build practices that are totally dependent on AI tools.

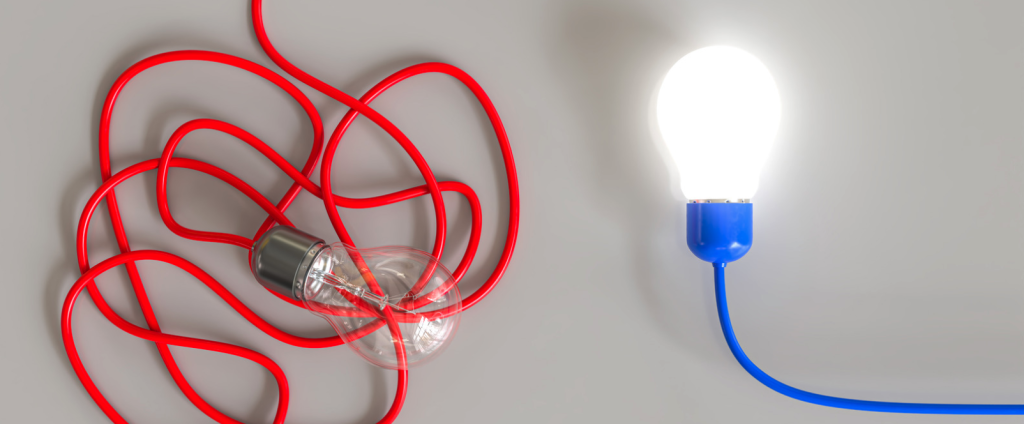

So smaller, more agile firms focussing on everyday audit work may well be advantaged by the distracted focus on AI by the large firms. We can choose tools that are helpful, transparent and predictable, let the big firms make the mistakes, while we continue offering services that are size-appropriate and provide personal service.

AI cannot replace judgement and ethics

It was agreed that the (human) auditor cannot outsource their responsibilities to AI to exercise judgment and act ethically. All who use AI extensively emphasised the importance of not just accepting results at face value but cross-checking sources and references. We need to assume that we are working with an intelligent, but precocious, over-confident, and inexperienced junior who needs very clear instructions, and constant vigilance on our part because of his tendency to make stuff up and feel no regret for doing so!

People at the event representing entities being audited expressed regret for the tendency for the human staff to rely too much on the technology and so fail to engage at a human level with the entity managers and governance. They missed the subjective gains from spending time face to face with an experienced professional.

This is I think where smaller, less tech-reliant firms can gain an advantage. We can stay relational where it counts and allow the computers to do the bits that they do best – fast processing of large amounts of data. Iain McGilchrist, celebrated psychologist and author of “The Master and His Emissary” describes in a related article why trying to mimic the human brain with AI is a problem:

“AI—artificial information-processing, by the way, not artificial intelligence—could in many ways be seen as replicating the functions of the left hemisphere at frightening speed across the entire globe. The left hemisphere manipulates tokens or symbols for aspects of experience. The right hemisphere is in touch with experience itself, with the body and deeper emotions, with context and the vast realm of the implicit. AI, like the left hemisphere, has no sense of the bigger picture, of other values, or of the way in which context—or even scale and extent—changes everything.”

Dr McGilchrist describes in his book, written prior to AI emergence, the danger to a society of becoming so left-hemisphere dominant that we become self-referential, fragmented, disembodied and out of touch with what makes us human. AI can only emulate the processing part of the left hemisphere, so cannot represent true intelligence, which uses the whole brain, let alone exercise judgement and display ethics, except in a disjointed, legalistic way.

The desire for Agentic AI

At the Roundtable event “Agentic AI” was mentioned a number of times as the inevitable goal for the profession. This is another level above data complex data-mining and processing which is what LLMs (Large Language Models) do, towards a defined goal – an AI “agent” carrying out a complex task of series of tasks like an employee. It is:

• Goal-directed: Operates toward objectives and subgoals.

• Autonomous: Can take initiative without continuous user input.

• Stateful: Maintains internal memory or state to inform decision-making over time.

• Interactive: Capable of calling tools, interacting with APIs, querying databases, and coordinating other agents.

• Adaptive: Can respond to new information and change course mid-task if needed.

This is nice in theory, but from my perspective in a profession where ethics and accountability are central, outsourcing major tasks with real-world ramifications to an autonomous, adaptable, goal-directed, black-box presents potentially disastrous problems. The group seemed to agree that this is where the major risk of AI lies. One scenario suggested was that an agentic AI “junior” could introduce systemic error across all the jobs it was working on, and no-one would know. Until it was too late.

My suggestion that maybe we should focus our efforts on using the tech for rules-based analysis that had clear inputs and outputs verifiable by the auditor, and we let the humans do what humans do best, was not applauded. Nice try though.

Some other practical warnings

The big firms are very, very strict on not allowing client data to escape into the wild of unbounded AI. They restrict carefully where their AI is hosted (within their own cloud) and this is tested extensively and all use is documented. The lesson for us? Don’t expose identifiable client data to AI tools unless you are very sure that it is not being seen and gathered. This could get you in a Lot of Trouble.

The group identified a potential expectation gap between promise and delivery. In other words, if you are promoting your services as being extra-special because you use AI tools you could be setting yourself up for criticism when you discover that it’s actually a lot more complicated and expensive than you imagined, and where is this promised efficiency reflected in our bill?

It was suggested that firms have very strict policies on the use of approved tools, included in employment agreements and firm policies. But all the best policies, as all auditors know, don’t necessarily translate to day-to-day practice. And remember PES3/ISQM1 32(f))requires that any AI tool obtained or developed for use in performing audits must be appropriate and must be appropriately implemented, maintained and used. This should be documented in your Quality Manual. The engagement partner must take full responsibility for whatever processes and “agents” that they use, or those that are used by their team. So if someone on your team is trying to save themselves some time by throwing the audit file into ChatGPT and not telling you about it, guess what? It’s your problem.

There was also some concern expressed about the staffing gap which may emerge as junior work is replaced by AI agents. How will this bode for the future of the profession? How will new staff learn the basics?

Takeaways

The road to AI Audit Utopia is fraught with potholes. Auditors should apply their professional judgement and scepticism and proceed with caution. Being a small-to-medium firm is not necessarily a disadvantage. We will not be left behind, and we may indeed be sought out for our human-centred approach. Leave the big firms to make their mistakes and continue to do the basics well, knowing that for most entities, human auditors – with the help of transparent technology – will do just fine.

We will be exploring this in more detail at our conference, specifically looking at what readily available tools SME firms are using successfully and safely, and what Audit Assistant is doing to leverage AI tools safely and securely within our software.

Clive McKegg, December 2025

For some great practical guidelines see the AUASB article on the impact of AI on Auditors.